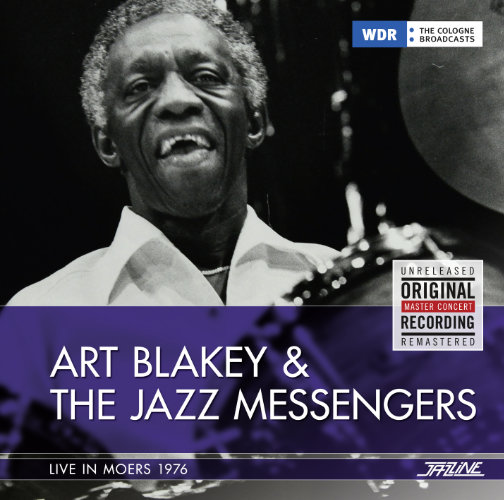

Jazzline N 77025 (CD) / N 78025 (LP)

ALSO AVAILABLE IN VINYL 180g DIRECT METAL MASTERING

live in Moers 1978

Blakey in Moers?? In MOERS???

Oh yes.

"Along Came Betty" and "I Can't Get Started" mixed with improvised music? Hardbopper amongst free spirits such as Cecil Taylor, Paul Rutherford, Misha Mengelberg, Yosuke Yamashita, Han Bennink, Evan Parker, Anthony Braxton and the Globe Unity Orchestra?

Why not?

"What seemed to be an out-of-place booking followed. Although I had loved Art Blakey's music since I first heard the 1958 gem 'Moanin', that hard-driving drummer's style was not an easy fit with the atonal and freely played sounds that dominated the festival." Impressions from the New Jazz Festival Moers 1978 by the American jazz-journalist and photographer Frank Rubolino.

Already two years earlier they were there: Ear- and eyewitnesses such as Rubolino, who considered the appearance of the Jazz Messengers on the Moers lineup as "misplaced" – "old jazz" (in this case a variety developed in the mid-1950s and consequently retained by its protagonists) in the context of a festival dedicated to – nomen est omen – the new jazz. "Risk taking" of a somewhat different kind?

Although Moers had already early on developed its own distinctive profile, this did not imply a dogmatic insistence on what is commonly labelled "free". Moreover, big names such as Art Blakey were crowd pullers and the live recording confirms the enthusiastic reaction of the audience to the band's performance. By the way, in 1979 the Jazz Messengers were not the only act conscious of tradition: Also the Elvin Jones Quartet and the Archie Shepp Quintet formed part of the festival programme – bands with an equally strong level of Afro-American aesthetics (something, which was always held in high esteem in Moers). Furthermore, Blakey was considered a musician who literally epitomised the history of jazz. The fact that the Messengers were back on stage in Moers only two years later shows that the organisers did not consider them to be "the odd man out".

The drummer never made a secret of his distaste for free jazz. Despite Blakey's more explosive and freer performance in the title song of the 64-album Free for All with Wayne Shorter, whose solos were borderline between hardbop and free jazz and can be described as an early version of free bop: The Jazz Messengers remained the embodiment of hardbop, style-forming and maybe the most popular band of their genre. Above all, they were as a band an institution, in business for three and a half decades and a one-time home for countless musicians – truly a who is who of jazz.

In 1976 a transitional period was coming to a close. Compared to the previous ten years Blakey was recording less, even dramatically less when compared to earlier times. Although the band's name continued to exist and kept repeating its repertoire – when it came to personnel, the Jazz Messengers were anything but constant: Continuous changes of the lineup were almost a daily routine. This had the consequence that almost no band-lineup could get close to the coherence of earlier editions. Only in 1977 Blakey assembled Messengers who would stay together for a while again, three years in total: Trumpeter Valery Ponomarev,

tenor David Schnitter, alto-saxophonist Bobby Watson, pianist James Williams and bassist Dennis Irwin – together with them the bandleader returned to Moers in 1978.

In 1976 the cooperation between Blakey and Dutch impresario Wim Wigt started. Increasingly, Wigt opened up the European market for the Messengers and released several Blakey-recordings under his own bop-focused label Timeless Records. All this during the heydays of jazzrock, when acoustic, swinging, straight-ahead jazz had a difficult time and suffered from a decline in public interest. This should change again a few years later with neobop, with musicians for whom the Jazz Messengers had served as a springboard: Terence Blanchard, Donald Harrison, Wallace Roney, Mulgrew Miller and – leading the way – Wynton Marsalis.

Even during a tour limited changes in the lineup could occur, for instance in the summer of 1976. One day prior to the performance in Moers, Woody Shaw replaced the indisposed Bill Hardman. During the previous weeks the piano was alternatingly played by Walter Davis Jr., John Hicks and Mickey Tucker. Chris Amberger performed instead of the previously announced bassist Yoshio "Chin" Suzuki (by the way, Amberger was a link to the independent scene, as shortly before he had worked with Anthony Braxton and Leo Smith, who also appeared on stage in Moers).

This personnel merry-go-round meant that Blakey could not always gather young musicians around him as was his image. In Moers he performed with several generations of musicians: Tenor David Schnitter was 28, pianist Mickey Tucker 35, Bill Hardman (who had already worked with Blakey in the late-1950s) 43 and the bandleader himself was 56 years old.

Three months earlier the band had recorded the album Backgammon in New York. The Moers-concert opened with the title song from that album, a burner, which set the tone for the entire programme. For only two minutes twenty, "I Can't Get Started" was what it originally had been, a ballad – subsequently it continued in a much more powerful style. This was followed by a song Blakey could not afford not to play – the "Blues March" also steamed along in Moers. After the second Benny-Golson classic "Along Came Betty", two compositions by Walter-Davis, Jr. – "Gypsy Folk Tales" and "Uranus" - brought the set to a close. Both of them were a tour de force, pure hardbop.

A few weeks after the appearance on the Lower Rhine the drummer was interviewed by the British journalist Mike Hennessey. Blakey explained to him why so many musicians spent only a short period of time in the band: "I told them to go and get their own band, I thought it was time for them. And they would go doing well. They didn't want to leave, they wanted to just hang on. I said, 'look, we're not having a Modern Jazz Quartet thing!'" With regard to personnel – JM - the Jazz Messengers were a true antipode, a counter project to MJQ. This is even more the case with regard to aesthetics – with their hard-drivin', hard swingin', hard bop thing.

Karsten Mützelfeldt